Language as a Human Monopoly

By J. Michael Strawn

In 1 Samuel chapter 13, we read the account of King Saul who was in a situation in which he ran out of time and decided to take action, even though he had been commanded to wait. While we might say that he was trying to bring about a result that had God in mind, Samuel the prophet condemned Saul, even to the point of telling him his kingship would come to an end because of his actions. By seeing how Saul and others in the Bible handled situations we might call “dilemmas” or even “crises,” we can generalize some rules and strategies we can employ in difficult situations. The most foundational ways we can assess such situations and then take action, however, start at the level of thought and speech, long before we move to action in the situations.

In 1 Samuel, Saul saw his situation, that of delaying and not offering sacrifices after a battle, as a crisis. Instead, he should have seen it as a situation in which he could exercise faith. There are some reasons why he acted that way, and why we tend to act similarly.

First of all, there are at least two components of crisis: a) physical (the elements making up the dilemma) and b) temporal (those elements associated with – and usually exacerbated by—the passage of time). Since a crisis is by definition a situation that seems to swamp an individual, it is axiomatic that we find ourselves helpless to change the situation. However, we do have the power to map representations onto the situation, even

if we cannot change it.

King Saul assessed the situation at Gilgal as a crisis, and then he acted upon that situation as if it were only a crisis. His words reveal that he thought he had no choice but to make the sacrifice when he saw his army “melting away.” This gave it legitimate crisis status in his eyes, but this was a mistake: It was a point at which he could have brought about

lasting results by exercising faith.

After Saul made the sacrifice, Saul went out to greet Samuel. But the king did not even get a chance to speak. Samuel’s greeting was stern: “What have you done?”

Saul could have chosen to represent his dilemma as an opportunity to show faith, not as a crisis. But he was not alone in facing such a crux decision. There are examples throughout Scripture where other people did the same:

• 2 Samuel 24 – David took the military census because he saw it as a potential crisis, and not as a point to exercise faith, even though he was encouraged to do that by his faithful counselor Joab.

• Daniel 3 – The three Hebrew men, Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah, didn’t treat the situation at the fiery furnace as a crisis, but a point at which to exercise faith.

This decision saved them.

• Daniel 6 – Daniel facing “certain death” in the lion’s den did not treat the

situation as a crisis, but as a point at which to exercise faith. This saved him.

• 1 Samuel 17: David arrived at the battlefield and everyone there believed the situation had reached crisis status. But David correctly understood the situation as something far beyond its temporal and physical elements.

• 2 Chronicles 20—King Jehosophat looked at the challenge of the enemy army at Engedi not as simply a crisis. We know this because his first response was to call everyone to the temple, to seek God. His response took time and thoughtfulness (and reveals his underlying character and relationship to God.)

• Exodus 14—The Israelites represented the Red Sea situation as a legitimate crisis, but not a faith situation. They were short-sighted in their belief that the God who had brought them to the shores of the Sea could not take them across it.

• Exodus 14 – Again, even though they had been saved from many “crises,” which the Lord and Moses represented as opportunities for great faith, the Israelites at Mara looked at the bitter waters and believed them to be a crisis.

• Exodus 17—The same was true when the Israelites faced an absence of water at Rephidim.

• Genesis 25 – Esau saw his immediate situation as a crisis. For him, it was simply a case of being desperately hungry, not a point at which to exercise faith. In Hebrews 12:16, God said that his decision revealed him to be godless, for he acted as if a crisis created a reality in which God and His interests didn’t matter.

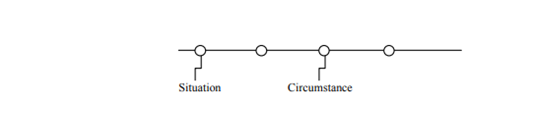

All of these examples teach us that, although any situation or circumstance certainly has temporal and physical elements, those elements alone cannot form a crisis. From the examples above we can see that each situation had overwhelming physical and temporal aspects. But what makes a situation become a crisis in someone’s mind is another aspect—a “designating element.”

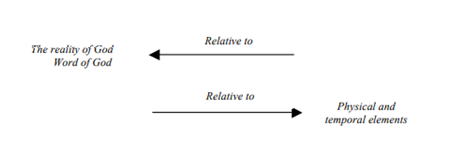

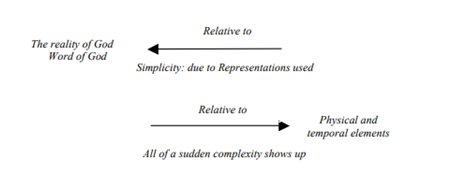

A designating element is a representation of the physical and temporal elements: a representation we use to determine or designate it. The terms associated with crisis are all terms relative to the temporal and physical elements. This is nearly universal—when people speak of something as a crisis, they speak of it in terms of its physical and temporal elements.

But the terms associated with the exercise of faith are different! They are not relative to or associated with the temporal and physical elements that make up the situation. They are relative to God, and to the Word of God.

A person cannot do both. We want to do both, but it is not possible. We would like to use common sense, be rationalistic, be pragmatic – and be spiritual. But the Bible teaches that these two mindsets and ways of representing situation cannot be employed at the same time. If we look at how the three Hebrew men facing the fiery furnace represented their

situation, they acknowledged the reality of the threats of the king and the potential of their own deaths, but discounted them as compared to the reality of God and their own opportunity to show faith in the situation.

When people use representations of situations that focus on the temporal and physical elements of them, they add complexity to their thinking. They begin to feel swamped and confused by all of the factors involved. In 1 Samuel 13, King Saul wanted to avoid using terms relative to Word of God and the reality of God. Waiting was simple, and he was told to do this. But he thought that waiting was too simple, that i would underestimate the crisis. He as a leader couldn’t do that, he thought. Consequently, using only terms relative to the Word of God and to God Himself, he believed, would have underestimated the situation. However, King Saul’s assessment was actually an underestimation of faith and what it could do.

If a person decides to treat each distressing episode, represented in the thematic as a node on the timeline, as a point at which to exercise faith, the power of the crisis potential of that situation lessens. The decision is this: Do I assess this situation by its crisis potential, or as an opportunity for faith?

A person who assesses a situation as an opportunity for faith would change his or her behavior as a result of a change in language. Such a progress would take the following steps:

- 1) Begin with a decision to avoid using terms relative to the physical and temporal elements of a situation. If you do that, your mind will assign to their proper and inherently-less-useful status such ideas as common sense, pragmatic terms, experience, and what’s “practical.”

- 2) In thinking and speaking, exclusively use terms relative to the reality of God and the Word of God. In all the previously-cited examples from Scripture, when people used such terms, this triggered a supernatural element that changed the situation. Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah’s statements of faith actually involved God in their situation in a very literal way, as did the words of Daniel facing the lions’ den. These examples lead to a question: Is there a danger to a Christian when he or she overestimates faith?

- 3) Because talking about a situation in terms of its physical/temporal qualities is not the same as using terms that represent it as an opportunity for faith, and because the Bible says it’s not possible to do both at once, we must maintain and emphasize the contradiction between the two. Terms relative to God and to the Word of God must be elevated over time and experience.

- 4) You must use language abstracted from the Word of God, and only from the Word of God. When you use language abstracted in this way—that is, generalizations – you eliminate human wisdom and its supposed power.

- 5) You must commit to not create a “crisis.” This is a mental posture that requires vigilance. Saul he thought he was being responsible, exercising true leadership, being visionary, wise, and practical; fulfilling his obligation as a king. But what he did was take a situation ripe with opportunity to exercise faith, and ratcheted it up to crisis status with his action.

Often in a crisis there is a tendency to think that things are intractable without human involvement. Nothing will change until I act, we think. But is that true? Biblically, it is not true. These passages teach us that all things are tractable, changeable, and redeemable if one has true confidence in the reality and the Word of God. When we define something as a crisis, we essentially pronounce it to be intractable without using human experience to “solve” it.

Quite to the contrary, acting in faith triggers two things: first, the direct involvement of God in the situation, and consequently the elimination of human “wisdom.” We see in Daniel 4:37, after Nebuchadnezzar was humbled by God, the king acknowledged that God’s power put an end to anything he would have thought or speculated: Human wisdom was eliminated in the face of God’s power in situations. We must expunge the

idea that an situation or circumstance is intractable without human experience.

Someone might say that we must have sympathy on Saul, in the grips of a dilemma, damned if he takes action, and damned if he did not. Similarly, Abraham and Sarah believed they were in a dilemma, waiting for a promise from God to be fulfilled but both of them beyond the biological pale of parenthood. The same was true of Jehosophat in 2 Chronicles 20, under imminent siege by a foreign army, damned if he takes action, damned if he does not and does something as seemingly nonproductive as going to the

temple to discuss the matter with God.

But when you use terms only relative to the reality and the Word of God, you don’t deal with something as a dilemma. The concepts of dilemma and crisis are akin to one another, because in both we want to use terms relative to the ingredients of the dilemma.

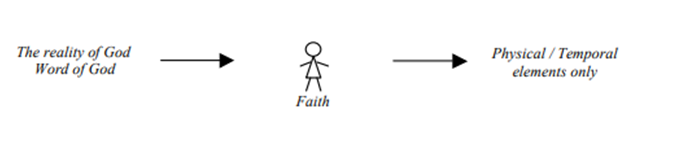

Faith eliminates or bypasses the terms relative to the physical and the temporal – though, of course, it does not eliminate nor bypass the physical and temporal themselves. This is not a small distinction. At Kadesh Barnea in Numbers 13 and 14, for example, the act of faith from Joshua and Caleb was to use their language in such as way as to bypass the terms relative to the physical and temporal aspects of the situation. “We should surely go

up!” they said, because of what a very real God had said previously about their eventual success.

However, many of our brethren become angry when we use only terms relative to the reality of God and the Word of God and reject the terms relative to the physical and temporal. In the case of Joshua and Caleb, their “faithful” language made the crowd they addressed homicidal.

Why were people so angry in similar situations in Scripture?

• In Exodus 32, at the foot of the mountain.

• In John 6, when Jesus decided to test Philip—Philip used only terms relative to the physical and temporal regarding the feeding of the five thousand.

• David’s brothers in valley of Elah were angry with his plan to fight Goliath.

• Joshua and Caleb, in their representational explanation, bypassed and eliminated terms of the physical and temporal, and didn’t deny the existence of the situation – and yet they were at the point of being stoned. This is echoed in the reaction of the listeners of Stephen’s address – except they did stone him.

• Why, then, is the use of language that bypasses and eliminates the physical and the temporal a death offense?

We see that only using terms relative to the reality and the Word of God polarizes human will and human experience. Why the anger?

1) It removes human options. Someone facing a health crisis is reluctant to give up medical options in favor of language relative only to the reality and Word of God.

2) It forces reliance on the unseen, and we hate that. It makes us nervous. It scares us. But using terms to link the reality of God to the situation while making us uncomfortable is nonetheless a basic function of faith. It takes focus to bypass, to walk away from and eliminate, all language relative to the physical and temporal elements of a situation.

But others were able to do it. In Matthew 4, Jesus was tempted and was in a true crisis situation. However, the temptations of Satan had one aim: to get Jesus to act directly on the physical and temporal elements of His hunger. Instead, Jesus deliberately used terms relative only to the reality of God and the Word of God.

In Genesis 16, Sarah appealed to Abraham on the basis of the physical and temporal aspects of her childlessness. Why did Abraham take her up on what we might call “the Hagar option”? Because he was unwilling to bypass and eliminate the terms that were relative to the physical and temporal elements.

Later, in Genesis 22, when Abraham was able to truly act in faith, he is able to do this by bypassing and eliminating all the physical and temporal terms that otherwise might have been used to characterize the situation.

In the parables of Jesus, we see the distinction between terms that are relative to the reality and Word of God, or to temporal and physical elements. Examples: the fish in the net, the sower and the soils, and others.

It is important to note that the Word of God and His reality put pressure on our language, much as a vise puts pressure on what it constrains. But if we begin with terms relative to the reality and the Word of God, language becomes a shared phenomenon, in which God and the self share the same language faculties. (The same idea is reflected in the Greek word for confession, homologeo, which means “to say the same thing” about a situation.)

Language that is a shared phenomenon with God is quite different from language monopolized by the self. In Numbers 13 and 14, the people were not able to let go of their own language about the situation. But Joshua and Caleb realized that the Word of God and the reality of God required that this monopoly on language be broken. In many churches we still rely on and insist on our own monopoly on language. Even worse, we drag the Text into our own monopolized language use.

Human monopoly on the language faculty is disastrous, both for individuals and on the corporate level. And it is an ancient folly: In Genesis 3, the serpent insisted that he would not share the language faculty with God, but that he would monopolize it and try to persuade Adam and Eve to do the same.

This happened in Exodus 32, at foot of the mountain when Moses delayed his return. The people monopolized language not only about their present situation, but about their past as well. This occurred in the days of Josiah, when the scrolls were lost. There was no shared language faculty with God, because His words were unknown to them.

This is one fault of liberal theology, which wants to monopolize the language about the things of God without sharing it with the Word of God. It is reflected in the writing of commentaries that are unwilling to share representational faculties with God and with His Word.

Here we draw the line. We cannot repeat the error of the Jews with Joshua and Caleb, nor the sin of David taking an unauthorized military census, nor the rage of the ones who stoned Stephen. When our representations are phenomena shared with the Lord, it triggers supernatural involvement. God, who tells us “not by might, not by power, but by My Spirit,” is waiting for us to trigger His involvement.

We conclude that learning from Scripture and growth in faith demand a sharing of the human representational faculty with God. But most are not willing to do it. Many are like the Jews, whom Jesus criticized because they did not know the Word of God, nor His power.

If a person insists on the human monopoly of language in a situation, that situation will become a crisis.

Is He involved or not? What will we say about this?

If we share our language with the Lord, we share the circumstance with the Lord.